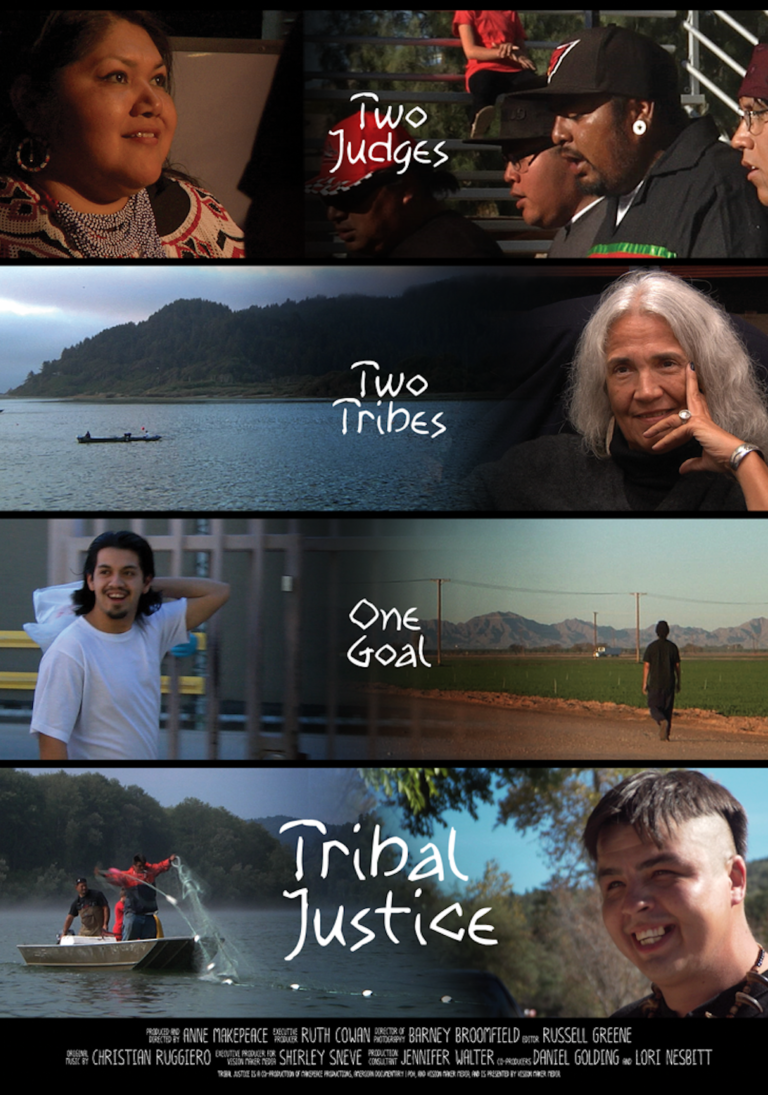

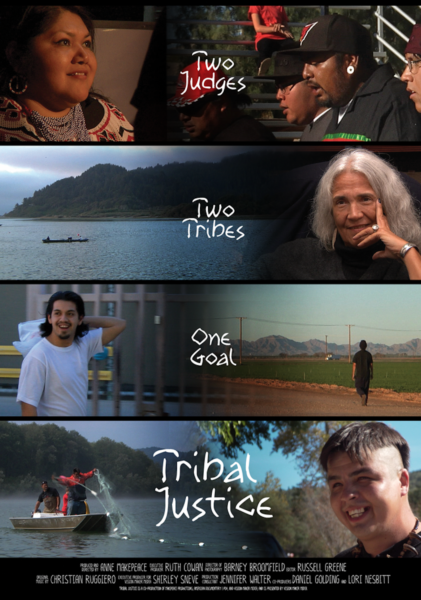

Two strong Native American women, both chief judges in their tribe’s courts, strive to reduce incarceration rates and heal their people by restoring rather than punishing offenders, modeling restorative justice in action. Tribal Justice is a feature documentary about a little known, underreported but effective criminal justice reform movement in America today: the efforts of tribal courts to create alternative justice systems based on their traditions. In California, the state with the largest number of Indian people and tribes, two formidable Native American women are among those leading the way. Abby Abinanti, Chief Judge of the Yurok Tribe on the northwest coast, and Claudette White, Chief Judge of the Quechan Tribe in the southeastern desert, are creating innovative systems that focus on restoring rather than punishing offenders in order to keep tribal members out of prison, prevent children from being taken from their communities, and stop the school-to-prison pipeline that plagues their young people. Abby Abinanti is a fierce, lean, elder. Claudette White is younger, and her courtroom style is more conventional in form; but like Abby, her goal is to provide culturally relevant justice to the people who come before her. Observational footage of these judges’ lives and work provides the backbone of the documentary, while the heart of the film follows offenders as their stories unfold over time, in and out of court. Taos Proctor, a young Yurok man who was facing a third strike conviction with a mandatory life sentence when we began filming him in 2013, has become a landmark case in Abby’s court. Over the past two years, we have filmed him struggling to remain clean and sober, and to rebuild his relationship with his partner and their young son. A teenage Quechan boy, Ryan Marks, is reunited with his extended family with the help of Claudette’s court. In contrast, Isaac Palone, another Quechan teenager recently released from a group home, is facing two felony burglary charges. Because his case is in state court rather than tribal court, he is at great risk of being funneled into the school-to-prison pipeline. Meanwhile Claudette works to reunite a nine year old boy, Dru Denard, with his family by invoking the Indian Child Welfare Act. These and other stories unfold over time, engaging viewers with the dedication of the judges, the humanity of the people who come before them, and a vision of justice that can actually work. Through the film, audiences will gain a new understanding of tribal courts and their role in the survival of Indian people. The film will also inspire those working in the mainstream legal field to consider new ways of implementing problem-solving and restorative justice, lowering our staggering incarceration rates and enabling offenders to make reparations and rebuild their lives.

Summary info for schedule – will be hidden on film page

Tribal Justice

87-minutes

Screening day / time

Tribal Justice

Tribal Justice

Filmmaker Notes:

This is the Filmmaker Statement I wrote for POV:

I have always been interested in Native American stories. My last film, We Still Live Here, which aired on Independent Lens in 2011, is about the revival of a Native American language that had disappeared for a century. In 2012, Ruth Cowan, executive producer of Tribal Justice, approached me with the idea of making a film about the innovative work of tribal judges in California. I was hesitant, because I didn’t know anything about tribal courts. I agreed to go on a research trip to meet two judges, and right away I was smitten. Abby Abinanti, chief judge of the Yurok tribe, which is the largest in California, awed me with her fierce intelligence; Claudette White, chief judge of the Quechan tribe, who live near Yuma, Ariz., impressed me with her commitment to justice. I was very moved by their dedication, by the obstacles they face in bringing justice to their people and by their passion for their work and their determination to apply customary tribal law in order to heal those who come before them. I knew that a film about their work would have all the elements of a great documentary: compelling characters engaged in important social justice issues unfolding dramatically over time. I also realized that the film would educate a broad audience about a subject unfamiliar to most Americans—tribal courts—and that it could have tremendous positive impact on our criminal justice system.

And so began the four-year odyssey of making Tribal Justice. On our first shoot, in April 2013, we were fortunate to film Taos Proctor in his first hearing in Abby Abinanti’s tribal court. Proctor, a young man of 26, was facing life in prison for drug-related offenses. Abinanti had convinced the state court to give her jurisdiction over his case for a year so that she and her staff could oversee his treatment and reintegration into the tribe. We followed Proctor’s story for two years as he struggled and ultimately succeeded in rebuilding his life.

While both Judges Abby Abinanti and Claudette White were open to having us film in their courts, most of the people coming before White’s court were not. It took two years to find a case to follow in the Quechan Tribal Court. We wanted to find a case in which a child was reunited with family through the Indian Child Welfare Act, and at last we met 9-year-old Dru Denard and his mother, Elaine, who were open to having us tell their story. Elaine Denard had lost Dru to the state a year before when she asked for help with his epilepsy and autism. When we met her in November 2015, she was desperate to get him back. We returned many times to film their story as she petitioned the tribal court to take over jurisdiction of his case and help her bring her son home.

White herself opened up about her personal life, and we were able to film the very compelling story of her teenage nephew, Isaac Palone, who came to live with her in the summer of 2014. When White was in high school, Palone was born in her family’s house to her teenage foster sister, a meth addict who left the home shortly thereafter. Palone was raised by White’s family until he was 9, when his biological mother wanted him back. She was still alcoholic and meth addicted, however, and she and her partner abused the boy for two years, until he was eventually taken from her and placed in group and foster homes. There, sadly, the abuse continued. Finally, at the age of 16, Palone returned to the reservation and White took him into her home. In the course of the film, she is able to get legal custody of Palone through her tribal court, but then discovers that he has outstanding convictions in the state system for breaking into cars. Because his juvenile delinquency case is in state court rather than tribal court, he is at great risk of being funneled into the school-to-prison pipeline.

On a final note, here’s something that Abby Abinanti wrote the day after the 2016 presidential election:

We, our people, have been here before… and as before we will stand for what is right and good…. They will come for us and others and we will not turn our backs on those who need our protection…. We may not win but we will not quit…. We will never forget our sacred responsibility to all as we have been taught by our creator and as we have promised our ancestors…. Stay strong, my family.

That kind of wisdom and resilience is so deeply moving to me, and the example set by these judges, who never give up, inspired me to keep going with the filming process and to complete Tribal Justice. And now my hopes for the film are actually happening! As Timothy Connors. Presiding Judge. Washtenaw County Peacemaking Court has written about the finished film, “Tribal Justice is an eloquent song, a song of resiliency and hope. It is a song that needs to be sung in every state court justice system. In this film, Tribal Judges Abinanti and White show us how.”